The Quarry Pond in Crinkill and Its Associated Tragedies

- Stephen Callaghan

- 1 hour ago

- 6 min read

Housing a large body of people in one place requires many considerations, and a reliable water supply is among the most important. When the permanent stone barracks was constructed at Crinkill between 1809 and 1812, the adjacent quarry, located in what would become the barracks drill ground, known as the Fourteen Acres, supplied much of the limestone. Once extraction ceased, the quarry was allowed to flood, fed by natural groundwater and rain, and, according to some contemporary sources, by a spring. Whatever the precise source, the resulting quarry pond became the barracks’ principal supply of water.

For a substantial pond that existed for more than 130 years, remarkably little has been written about it. No published account explains how it functioned as part of the barracks waterworks or how it shaped daily life in Crinkill. The aim of this article is to reconstruct the history and use of the quarry pond, and to acknowledge the tragedies associated with it.

The quarry itself had produced a substantial quantity of limestone, the bedrock of the Midlands, formed over 360 million years ago. Once quarrying stopped, the ready‑made basin filled naturally. A pump house was constructed, and pipes were laid to carry water to the barracks sometime before the first six‑inch Ordnance Survey map was surveyed between 1825 and 1846.

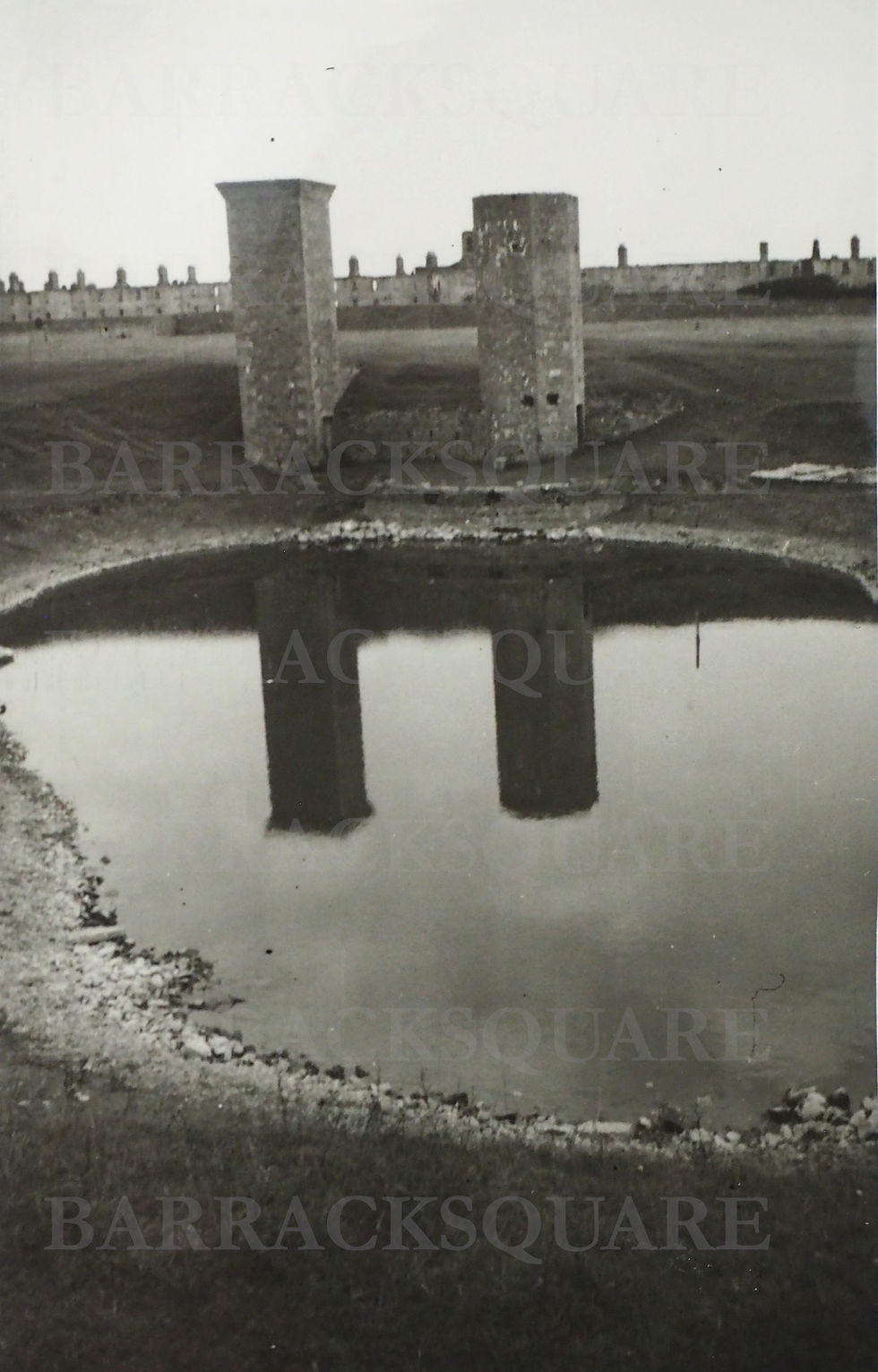

Based on that map, the quarry pond covered roughly 1,750 square metres, a sizable body of water. Contemporary accounts even claimed depths of up to 25 feet. As technology advanced, so too did the process of supplying the barracks with water. By the end of the nineteenth century, the quarry pond had effectively become a dedicated waterworks. Water was drawn from the pond and passed through filter beds, almost certainly slow sand filters composed of fine sand and graded gravels, which removed turbidity, reduced pathogens, and modestly improved taste. After filtration, the water was stored in a tank and then pumped to a reservoir or tank house via the pump house. A photograph from the 1940s shows both buildings, each standing roughly twelve metres tall: the pump house built to accommodate the long pump rods, and the tank house raised to provide sufficient water pressure.

By the time the 25‑inch map of Ireland was completed in 1913, the pond had reduced to around 1,100 square metres, still substantial, considering an Olympic swimming pool is 1,200 square metres. Reports from the period give the depth as seven to eight feet, rather than the earlier twenty‑five. Army medical records from the intervening decades suggest that the supply was often insufficient during summer months. When Birr began planning its own municipal waterworks, the barracks expressed interest in being connected.

As a large and accessible body of water, the pond inevitably attracted soldiers and civilians who used it for bathing and swimming. Unfortunately, over its lifetime the pond was responsible for five recorded drownings. It is fitting to recount these events, both to honour the individuals involved and to acknowledge the risks the pond posed.

The first recorded tragedy occurred in June 1823, when a father and his four sons went to the pond to bathe. The eldest son got into difficulty in deep water, and in the attempt to save him, a younger brother and the father were also pulled in. All three drowned. The incident was widely reported at the time, including in the Southern Reporter and Cork Commercial Courier on 28 June 1823:

“MELANCHOLY ACCIDENT. – On Saturday morning the 14th instant, about the hour of nine o’clock, the father and four sons of the name of Molloy, residing on the lands of Clonakilty, within one mile of Parsonstown, went to wash in the quarry where the stone for the Birr Barracks was raised, the eldest son, Edward Molloy, stript, and going on a cliff went too far and got suddenly into twenty feet water. The next brother seeing his situation went to his assistance, the father holding him by the hand, but, melancholy to relate, the second son pulled in the father, and the three were drowned in the presence of two younger brothers, one ten, and the other 12 years of age, who could render them no assistance; they were not got up for two hours. The father, J. Molloy, aged 45 years; the eldest son Edward, 23 years; the second, Patrick, about ten years. Molloy has left a widow and seven children to deplore his loss, the eldest only twelve years old. They lived on the estate of Simpson Hackett, Esq. of Riverstown, and were his tenants. – Dublin Paper.”

Some details in the article are inaccurate, but the sequence of events is credible. The Molloy family appears in the 1822 census living in No. 8, Lower Clonkelly, Birr. The household consisted of John, aged 48 and listed as a farmer; his wife Bridget, aged 36; and their children Edward (16), Denis (12), Thomas (10), Bridget (6), Catherine (5), Mary (4), Patt (14), John (0), and Honora (13). The tragedy remained in local memory for decades and was even referenced in the death notice of a distant relation in 1907.

The second recorded fatality occurred at about 10:30 a.m. on Sunday, 19 March 1876, when thirteen-year-old Anne Wright was seen walking towards the quarry pond carrying a can, presumably to collect water. Witnesses later recounted how she disappeared from view. With no sign of her, the police were called, and after a two‑hour search her body was recovered from about eighteen feet of water. An inquest ruled her death accidental. Her death certificate records the cause as “drowning sudden.”

The final recorded incident took place on 6 August 1909, when nineteen‑year‑old Private John Stephens got into difficulty while swimming. By this time a fence had been erected around the pond, suggesting an attempt to discourage bathing. His death was reported in the Daily Express on 10 August 1909:

"BIRR DROWNING ACCIDENT, SOLDIER’S TRAGIC DEATH,

(FROM OUR CORRESPONDANT) Birr, Monday,

An inquest was held to-day touching the death of Private John Stephens, of the Leinster Regiment, who drowned while bathing in a pond in the Fourteen Acres yesterday evening. It appeared from the evidence that the deceased was an expert swimmer, as well as a noted diver. On the evening in question he got into the water at the pond, the depth being between seven and eight feet. He swam about for some time, and subsequently got out of the water to have a “plunge”. He remained under water for nearly two minutes, and meanwhile Privates Mulcahy and Burke went to his assistance. They did everything possible to bring the

unfortunate man out alive, but failed. All efforts at resuscitation were unsuccessful. The jury returned a verdict to the effect that the deceased died of drowning and they added a rider recommending that the gallant efforts of Privates Mulcahy and Burke to save the deceased should be brought to the notice of their superior officers. The jury also drew the attention of the authorities to the state of the fence around the pond."

Stephens was born in Dublin, and had enlisted in the 4th (Special Reserve) Battalion, Leinster Regiment on 27 March 1909, having previously worked as a wagon man. His death certificate records the cause as “accidental drowning.” He was buried in the adjacent military cemetery.

No further fatalities are recorded. In time, the waterworks fell out of use. After the burning of the barracks, the pond, pump house, and tank house were abandoned. When the houses on Grove Street were demolished, the rubble was used to fill the pond. The pump and tank houses were likely knocked and used as infill as well.

Although the quarry pond no longer exists, it survives in local folklore and memory. In her local history books, the late Marjorie Joyce Kelly recounts how the pond was used as a dumping receptacle for unwanted items. Another story tells of a horse that drank from the pond, became ill, and died; when its stomach was opened, creatures were said to have emerged and slithered back into the water.

The quarry pond began as a necessity, supplying water to the troops at Crinkill. Yet it also became a place where people swam, bathed, and collected water, and, on several occasions, where lives were lost. Though long filled in, it remains part of the landscape of Crinkill, a reminder that even utilitarian features can take on deeper, sometimes darker, meanings over time.

Comments